FORRU-CMU: Origins and History

Origins

The starting point for the establishment of FORRU-CMU was the high rates of deforestation in Thailand in the 1970-80s, the logging ban in 1989, and the “Plook Pah Chalerm Prakiat Project” in the early 1990’s—a national initiative to plant native forest trees on 8,000 sq km of degraded land, to celebrate Golden Jubilee of His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej. Until then, tree planting in Thailand, had been mostly monoculture plantations of commercial tree species: pines, eucalypts, teak etc.; knowledge of how to plant and care for the vast majority of country’s 2000+ native forest tree species was lacking. Most had never been propagated in tree nurseries.

In 1992, Steve Elliott and Kate Hardwick were asked to assess a pioneering tree-planting project, implemented by a local NGO: “The Dhammanat Foundation”, near Doi Inthanon. The project was failing, because the tree species chosen were not suited to the site and weeds were smothering the trees. We recognized the need to build on the enthusiasm for tree planting that had been generated by “Plook Pah Chalerm Prakiat” by creating the skills and knowledge needed for proper forest-ecosystem restoration, to accelerate biomass accumulation, and recover forest structure, biodiversity and ecological functioning.

Consequently, a four-point research program was conceived: i) study forest regeneration mechanisms (particularly reproductive phenology), ii) nursery-based experiments, to learn how to propagate a wide range of native forest tree species and compile species production schedules, iii) field trials, to compare performance among species and test silvicultural treatments and iv) an international conference, to pool knowledge from the few scientists researching restoration at that time (run in 2000) and create a detailed research agenda.

After several years of fund-raising attempts, a grant was eventually procured in 1994 from RicheMonde Bangkok Ltd, to build a research tree nursery in Doi Suthep-Pui National Park HQ compound. FORRU-CMU opened for research in November 1994, under the co-directorship of Steve and Dr Vilaiwan Anusarnsunthorn.

An Idea Takes Root

Our initial research focused on developing a framework-species method, to restore upland evergreen forest (EGF) on Doi Suthep, having learned about the concept's generic principles in Queensland, Australia from Nigel Tucker.

“The framework species method (FSM) is a technique for restoring forest ecosystems by densely planting open sites, close to natural forest, with a group of woody species, characteristic of the reference ecosystem and selected for their ability to accelerate ecological succession.”

In the early 1990's, lack of knowledge was the main obstacle preventing effective forest ecosystem restoration. Most of the several hundred tree species, which comprise the diverse tropical forest ecosystems of northern Thailand, had never been propagated in nurseries. When to collect seeds; how to germinate them and how to prepare planting stock, ready for out-planting, were all unknown. In the field, which species to plant and how many; optimal stocking density; effective silvicultural treatments and how fast carbon might accumulate and biodiversity recover in restored plots had yet to be investigated.

The framework-species method provided a conceptual framework for the research program. Candidate framework tree species were first selected from amongst the indigenous EGF tree flora. We looked for tree species with high survival and growth rates, in exposed deforested sites, dense, broad crowns (that shade out weeds for rapid site recapture) and species which could attract seed-dispersing animals by producing wildlife resources at a young age (e.g., foods or safe nesting or roosting sites). The hypothesis was that planted trees would encourage animals to disperse seeds from nearby forest trees into the restoration plots. Seedlings of non-planted forest tree species that grew from incoming seeds (termed “recruits”) would reinstate natural forest dynamics and succession, accelerate biomass accumulation and catalyze recovery of forest structure and biodiversity.

Working with botanist, J.F Maxwell, most of the tree species characteristic of EGF on Doi Suthep were identified, resulting in a comprehensive herbarium collection (CMU-B Herbarium, CMU Biology Department) and a database, which included habitat preferences and altitudinal distributions of >600 tree species. Phenology studies, using labelled, identified trees in undisturbed EGF established optimal seed-collection times.

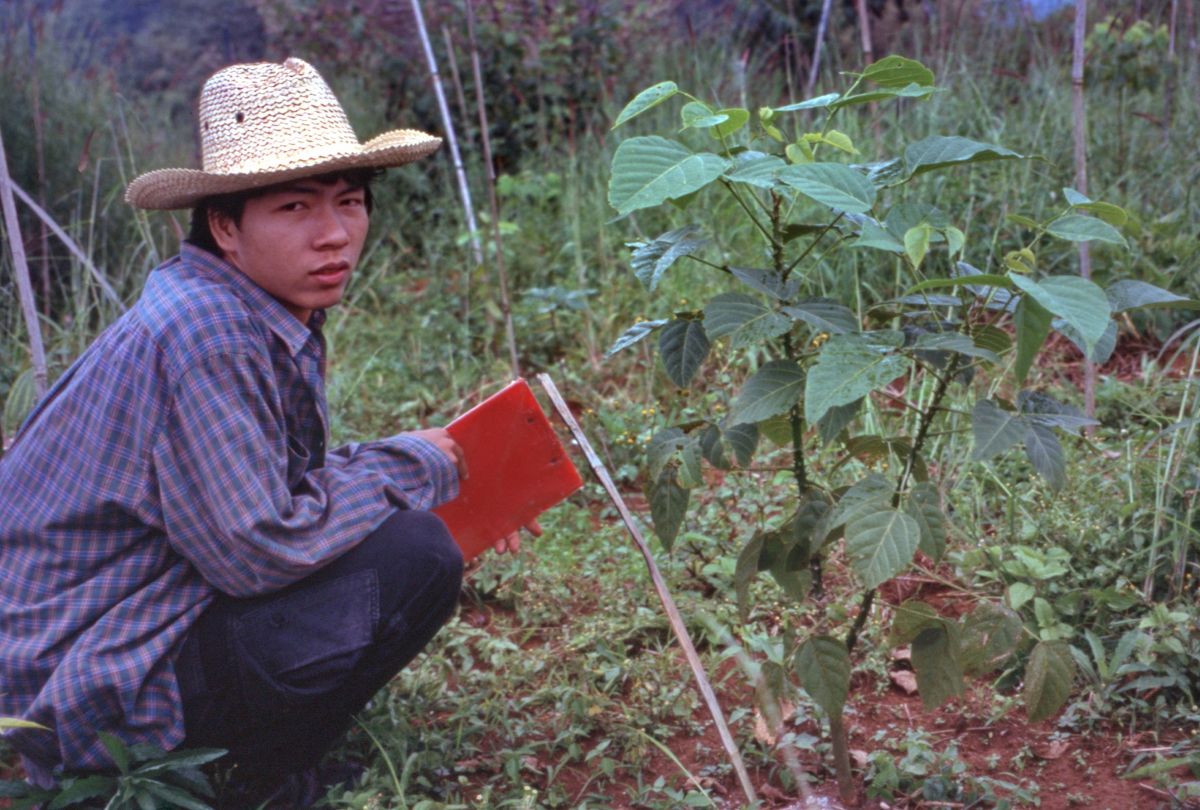

Nursery experiments, to overcome seed dormancy and manipulate seedling growth, resulted in “production schedules”, which detailed the most efficient treatments and timings required to propagate healthy, vigorous planting stock, of each tree species, by the optimal planting time. More than 400 tree species were investigated.

Field trials determined which tree species act as framework species, and how their performance can be improved by application of various silvicultural treatments (e.g., spacing, various weeding treatments and fertilizer application, mulch mats etc.). The experimental plots were established in the upper Mae Sa Valley, annually from 1996 to 2013, creating a chronosequence of immense research value.

So, does it work?

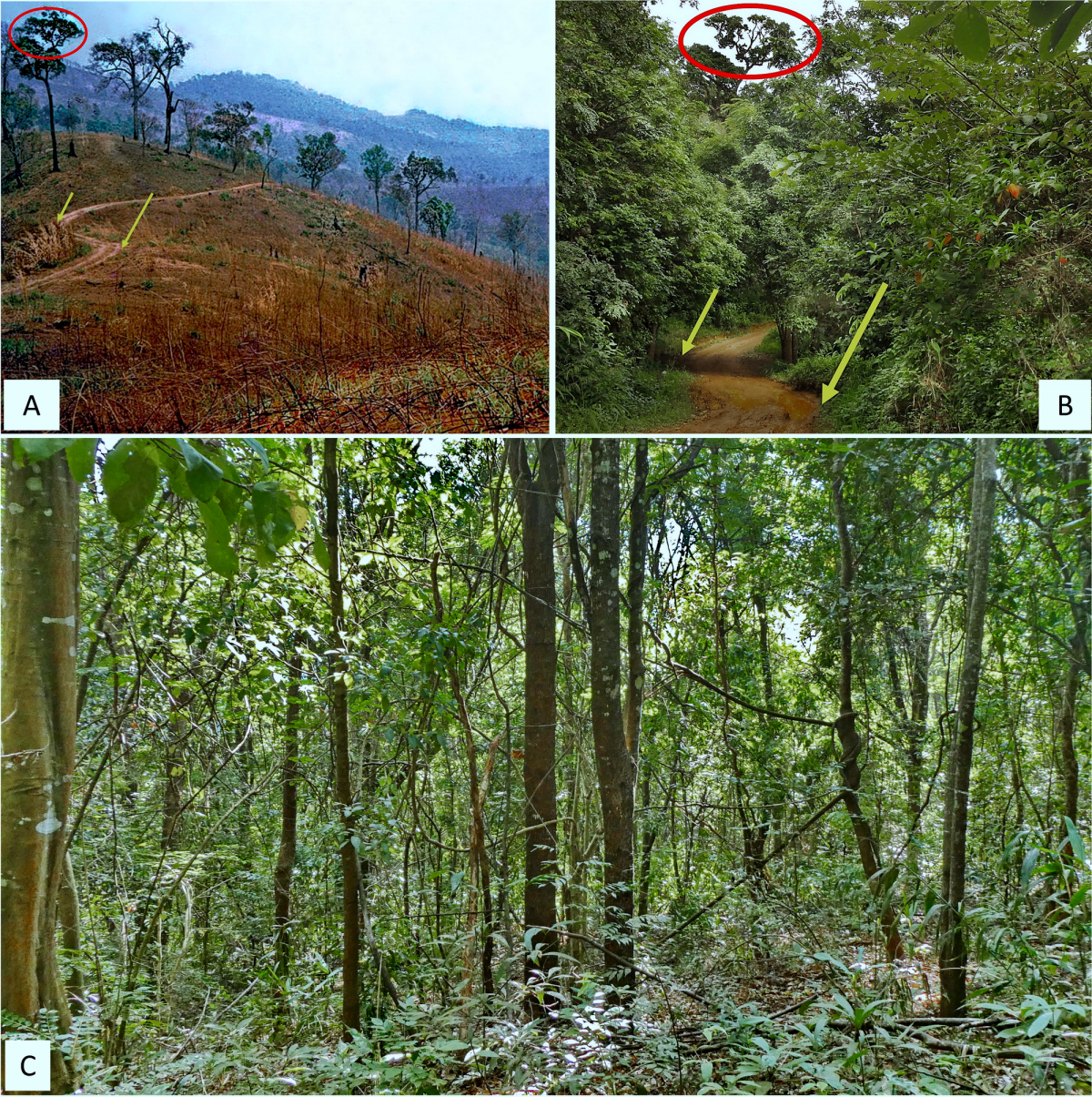

Using the identified species and treatments, canopy closure can now be achieved routinely within 2–3 years after tree-planting, and biodiversity recovery is rapid. The species richness of the bird community increased from about 30 before planting, to 88 after 6 years, representing about 54% of bird species recorded in nearby mature forest ... and the birds brought in tree seeds. Within 8–9 years, 73 species of non-planted (recruit) trees re-colonized the plot system, most having germinated from seeds dispersed there from nearby forest by birds (particularly bulbuls), fruit bats and civets. The species richness of mycorrhizal fungi, lichens and bryophytes also recovered rapidly, often exceeding that of undisturbed EGF.

Carbon—Forest Restoration's Ultimate Commodity

More recently, the chronosequence of EGF trial restoration plots was used to investigate how forest restoration contributes towards mitigating climate change through carbon storage. Net inputs of carbon into the soil from litterfall, overall accumulation of soil organic carbon and accumulation of above-ground carbon in the trees returned to levels, typical of old-growth natural forest, within 14–16, 21.5 and 16 years, respectively. We showed that the potential value of the carbon (if traded as carbon credits) was almost treble that of corn cultivation – a major driver of deforestation and source of harmful smoke pollution in the north.

Casting the Net Wider

Building on lessons learned from restoring evergreen forest, FORRU-CMU then applied a similar research protocols to develop equally effective techniques to restore lowland deciduous forest in northern Thailand, bamboo deciduous forest in Kanchanaburi Province (2008-2010) and lowland evergreen forest in Krabi Province (since 2005).

Passing on the Knowledge

FORRU CMU’s research outputs formed the basis of its education and outreach activities, providing a wide range of stakeholders with the skills and knowledge needed to implement successful forest ecosystem restoration, from school children and their teachers, to professionals from government and non-governmental organizations. The unit has hosted hundreds of school’s events and training workshops, both in Thailand and across the wider SE Asian region.

It has also published several practical manuals and other educational materials, in several languages, to generate maximum ecological and social benefits from its research program. Outputs include original technical advice on how to perform forest restoration, as well as generic protocols that enable researchers in any tropical region to develop effective restoration practices suited to local ecological and socio-economic conditions.

The Future of Forest Restoration?

The main thrust of FORRU-CMU’s future research will address the use of drones to enable cost-effective implementation of the unit’s research-based recommendations, over the wide-scales demanded by the current upsurge in global restoration projects. To this end, we ran an international workshop on “Automated Forest Restoration” AFR in 2015, which generated a research agenda, now being implemented.

FORRU-CMU will concentrate on these four agenda items: i) using drones to located seed trees, ii) developing techniques for drone-seeding to replace regular tree planting and iii) exploitation of trees’ allelopathic properties for natural weed control and the development of bioherbicides and iv) use of drone imagery to perform pre-planting site surveys and to monitor the progress of restoration (summarized in this video).

We put this slide show together for our 20th Anniversary. It presents a more detailed history of FORRU-CMU's first 2 decades. Enjoy!